订阅邮件推送

获取我们最新的更新

Why Did China’s Real Estate Policy Swerve?

1. Lujiazui Forum Sent an Important Policy Signal

Since June of this year, the Chinese government has sent many new signals on its real estate policy, particularly real estate financial policy. The implications of such policy signals warrant our attention.

The policy signals were fully released at the Lujiazui Financial Forum in June. “In recent years, some cities in China saw a steep rise in the household leverage ratio, and a large proportion of households reached an unsustainable level of indebtedness,” said Guo Shuqing, Chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), sternly, “to make things worse, around half of new savings went into the real estate sector. Apart from competing for credit resources with other sectors, excessive financing for real estate stokes real estate investment and speculation, giving rise to bubbles.” “History has proven that countries over-reliant on real estate to achieve and maintain economic prosperity all ended up paying a heavy price,” stressed Guo.

This message is of great importance for the following reasons:

First, the household sector’s indebtedness has become unsustainable. The implication is that future policymaking will strive to deleverage the household sector, or at least prevent the household leverage ratio from continuing to rise. The upward cycle of China’s real estate market since 2015 owes to increasing household leverage ratio. Household deleveraging will have obvious implications for the real estate market.

Second, the real estate market has occupied an outsize share of credit resources. The implication is that mortgage and development loans will come under tighter scrutiny.

Third, the economy should wean from overreliance on the real estate market.

Notably, Vice Premier Liu He, who is in charge of economic work, illustrated China’s macro-leverage ratio since the 19th CPC National Congress in 2017 with charts and figures at the forum. He presented three curves indicating the household, corporate, and government leverage ratios. While corporate leverage ratio has dipped and government leverage ratio nudged down, the household leverage ratio has spiked. “There are very complex structural and institutional factors behind this rising curve,” he noted, “we need to unravel the causes and take effective countermeasures.”

Liu’s speeches can be summed up with the following three highlights:

First, the decision-makers attach great importance to the rising household leverage ratio as a significant challenge to China’s economy.

Second, real estate is chiefly to blame for the spike in personal debts.

Third, senior leadership has decided to take action to address the excessive rise in the personal leverage ratio.

Both Guo and Liu mentioned real estate and household debt issues in their respective speeches, which is not by coincidence. The implication is that decision-makers have come to agree on the policy orientation of real estate. At least from official statements, China’s real estate policy orientation swerved in June. The CPC Central Committee Politburo meeting at the end of July has reaffirmed such a shift: After repeating the message that “housing is for living in, not for speculation” and calling for implementing the long-term mechanism for real estate regulation, the Politburo meeting has released a new statement: “We should not use real estate as a short-term means for stimulating the economy.”

2. What Led to the Shift in the Real Estate Policy?

Beyond doubt, China’s real estate policy has swerved. The questions are what are the reasons behind such a shift? Is it a short-term or long-term shift? To answer these questions, we must unravel the underlying reasons behind China’s changing real estate policy.

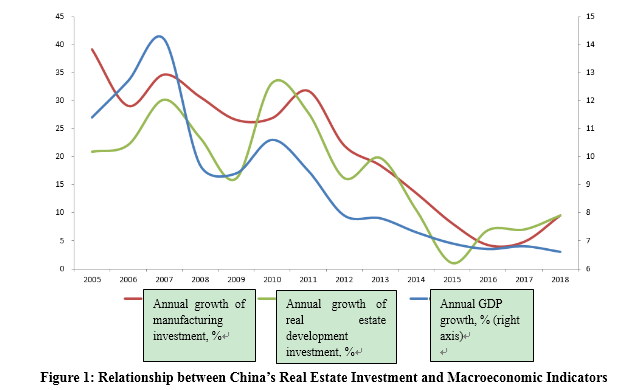

First, let us look at the relationship between real estate investment and China’s macroeconomic performance. The red curve shows the annual growth of manufacturing investment. The blue curve denotes yearly GDP growth. The green curve is the annual growth of real estate investment.

From a long-term perspective, the three curves are highly positively correlated. As can be seen from a few time points, China’s real estate stimulation in 2009 effectively led to a rebound in both GDP and manufacturing growth rates. After peaking in 2010, the three curves simultaneously dipped at the end of 2014 and early 2015 almost in parallel.

The divergence occurred after 2015. In early 2015, real estate investment growth approached zero, but swiftly rebounded under the effect of a host of stimulus policies, particularly policies that led to an increase in the household leverage ratio. At the end of 2018, real estate investment growth exceeded 10%. However, the other two curves did not rebound with rising real estate investment. In particular, GDP growth kept on the decline.

As can be seen from the chart, the relationship between the three curves started to change before 2015. Unlike in the past, the policy stimulus to shore up real estate investment failed to bring about an uptick in China’s economy. The divergence in the correlation of the three curves is attributable to the fact that real estate investment has lost its potency in propping up growth, so much so that the government no longer needs to resort to real estate to spur a slowing economy.

Here, I would like to cite the information from Professor Ni Pengfei at the National Academy of Economic Strategy, CASS to illustrate the underlying reasons behind this phenomenon.

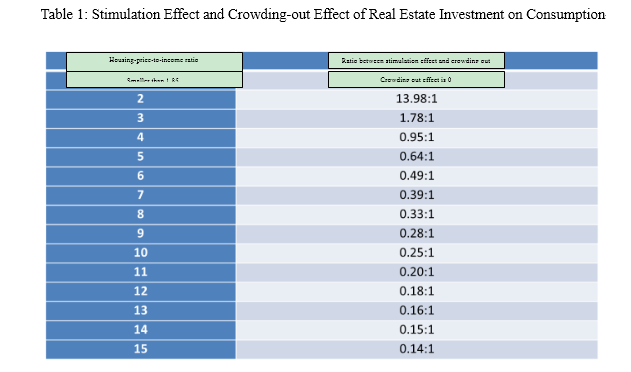

The first chart shows the real estate industry’s effects of stimulating and crowding-out consumption. Rising housing prices may boost and crowd out consumption at the same time; these effects vary with the housing-price-to-income ratio. The left column is the housing-price-to-income ratio, and the right column is the ratio between stimulation effect and crowding-out effect. As the table shows, when the housing-price-to-income ratio is 2, the consumption stimulation effect is 13.98 times that of the crowding-out effect. Lower housing-price-to-income ratio corresponds to a more significant consumption stimulation effect of rising housing prices. As the housing-price-to-income ratio increases, the ratio between growth stimulation effect and crowding-out effect will change as well.

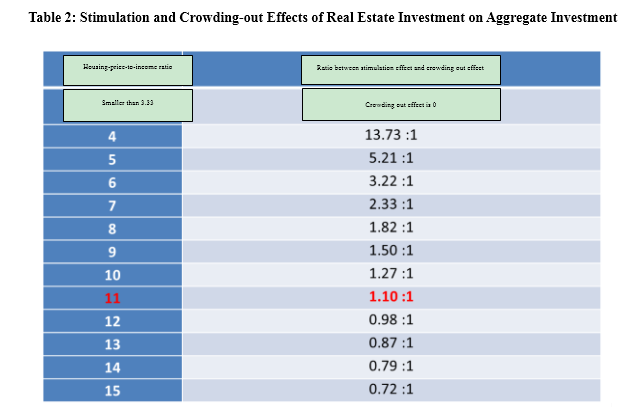

The second table shows the stimulation and crowding-out effects of real estate investment on aggregate investment. When the housing-price-to-income ratio exceeds 11 times, the stimulation effect of real estate investment would be smaller than the crowding-out effect.

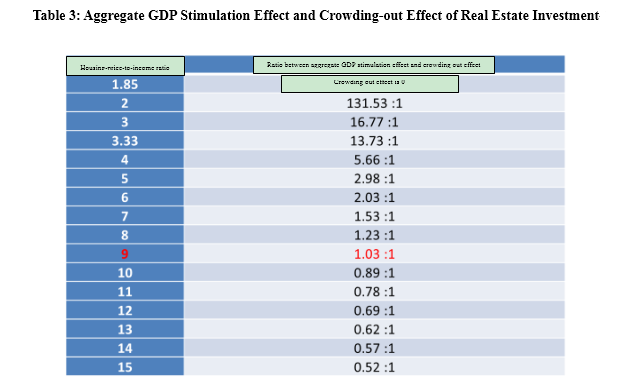

Based on the above two tables, it can be concluded that when the housing-price-to-income ratio is 9, the GDP stimulation and crowding-out effects of real estate investment on consumption are about the same. When the housing-price-to-income ratio exceeds 9, the negative economic growth effect of real estate investment outweighs the positive effect. In other words, when the housing-price-to-income is above 9 times, real estate investment will contribute negatively to the economy. By the end of 2018, China’s overall housing-price-to-income ratio stood at 9.1 times, which is highly consistent with the observed macroeconomic phenomenon. Given the complex relationship between real estate and the economy, this finding warrants further research and attention, but at least offers a clue for analysis on the impact of real estate investment.

3. Outlook on the Real Estate Policy

Based on the above analysis, our outlook on future real estate policy can be divided into the following two parts:

First, China’s real estate policy should tighten on all fronts in the short run. China should tighten mortgage loans by raising interest rates; bring real estate development loans under tighter control; offer window guidance on bond issuance by real estate firms by introducing a blacklist system; tighten overseas bond issuance by restricting the borrowing of new loans to repay existing loans; curb the flow of trust funds into the real estate sector (CBIRC No.23 Document); some large real estate developers are likely to default on debts, exposing their negative externalities and triggering a regulatory storm.

Second, China should restructure its institutional systems in the medium- and long-term, such as redesigning the housing system, restructuring the land system by amending the Land Administration Law, and overhauling its fiscal system. The amendment to the Land Administration Law implies a revolutionary change in the legal premise that underpins the real estate industry. After the housing reform of 1998, China’s real estate industry took another important shift with the amendment to the Land Administration Law in 2019. As local governments wean from land sales revenues, fiscal restructuring becomes inevitable.

作者相关研究

Author Related Research

- 银行股上涨是因为股息率高吗?

- 【NIFD季报】贸易战冲击全球股市,银行股新高之后存隐忧——2025年第二季度股票市场

- 关于居民提前还贷现象的分析

- 西班牙是如何应对房地产危机的

- 尹中立:化解风险是当前楼市政策的重点任务

- 尹中立:关于稳定房地产市场的几点建议

- 【NIFD季报】政策刺激促股市回升 重组概念股波动加大——2024年度股票市场

- 【NIFD季报】基本面逆转,A股再现“井喷”——2024Q3股票市场

- 【NIFD季报】基本面逆转,A股再现“井喷”——2024Q3股票市场

- 尹中立:征收房地产税的难点及对策

- 征收房地产税的难点及对策

- 货币政策如何支持住房租赁业发展?

- 【NIFD季报】股市走势分化 新规则引领股市凤凰涅槃——2024Q2股票市场

- 尹中立专栏丨需关注股市资金的虹吸效应

- 需关注股市资金的虹吸效应

- 【NIFD季报】监管新规开启A股新征程——2024Q1股票市场

- 不断完善“市场+保障”的住房供应体系

- 【NIFD季报】热门赛道股估值回归,“壳价值”升温——2023年度股票市场

- 政策发力有助于扭转房价预期

- 中证A50指数即将发布:入选股有何特别?

- 关注市场无风险收益率的变化

- 【NIFD季报】无风险收益率高启 资产价格承压——2023Q3股票市场

- 一线城市房价对政策调整作出积极反应

- 房企债务风险现状及应对策略

- 化解房企债务风险有助于市场复苏

- “只听楼梯响,不见人下来” 监管应统一调整存量房贷利率

- 存量房贷利率调整恰逢其时

- 【NIFD季报】股票市场冲高回落 房地产行业牵一发而动全身——2023Q2股票市场

- 房地产市场仍处于边际修复过程中

- 【NIFD季报】人工智能“一马当先”,“中字头”稳健前行——2023Q1股票市场

- 当前并非出台房产税政策的好时机

- 尹中立:全面注册制落地,“打新必赚”神话终结

- 注册制改革将使股票估值结构趋于优化

- 2023年股市是否会否极泰来?

- 【NIFD季报】全球黑天鹅事件频发,风险资产承压——2022年度股票市场

- 坚持房住不炒,有效防范化解地产领域风险

- 政策进一步发力,持续扭转房地产市场预期

- 【NIFD季报】美联储加息对A股市场产生冲击——2022Q3股票市场

- 海外房地产“负资产”的警示

- 美联储强力加息对全球资本流动产生巨大扰动

- 美联储强力加息对全球资本流动产生巨大扰动

- 新房销售面积是否会跌破10亿平方米?

- 建议降低按揭利率提振预期,设立住房稳定基金

- 稳定房地产市场,需要供给与需求同时发力

- 【NIFD季报】全球股市开启危机模式,A股逆势反弹——2022Q2股票市场

- 房地产市场已经进入新阶段

- 【NIFD季报】疫情反复与俄乌冲突对股市产生较大扰动——2022Q1股票市场

- 当前股市波动的五大因素

- 股市波动幅度过大是否与投资者结构有关?

- 导致当前股市超预期下跌的因素有哪些?

- 房地产金融政策释放暖意 “三稳”预期可期

- 当前股市超预期下跌探究

- 【NIFD季报】蓝筹股疲弱 壳价值“回光返照”——2021年股票市场回顾与2022年展望

- A股长期逻辑的“底气”:我国经济长期向好的基本面没变

- 2022年A股,到底会怎么走,还有何种机会?

- 2022年房地产市场能否出现V型反转?

- 如何促进房地产行业良性循环?

- 2022年中国房地产将难再出现V型反转

- 2022年房地产市场展望

- 2022年房地产工作重点是促进良性循环

- 融资改善将带动房地产行业企稳

- 商品房预售资金监管从严是大趋势

- 【NIFD季报】2021Q3股票市场

- 央行为什么要强调维护房地产市场的健康发展?

- 楼市快速降温 该如何应对风险?

- 房地产市场出现了拐点信号

- 炒房现象得到明显遏制,持续推动地产市场健康发展

- 贵州茅台股价上涨幕后的推手是谁?

- 【NIFD季报】2021Q2股票市场

- 近期部分城市房价上涨的原因及调控建议

- 定增破发成为股市常态并非坏事

- 土地出让金管理进一步改革 需与地方债风险化解改革措施配套

- 比特币存在三大缺陷

- 【NIFD季报】2021Q1股票市场

- 从人口流动特点看房地产市场四大趋势

- 尽快出台土地供应计划 有效引导房地产市场预期

- 今年房地产市场可能呈现五大趋势

- 投资银行如何适应注册制改革的要求?

- 如何有效杜绝经营贷流入楼市?

- 公募基金“抱团”式投资行为需要重新规范

- 集中供地政策对房地产市场的影响

- 资本市场监管如何适应自媒体时代?

- 股票市场的剧烈分化还将持续多久?

- 房地产市场的分化趋势值得关注

- 基金“抱团”致股价分化背后的制度反思

- 房地产贷款集中度管理对市场影响深远

- 首席经济学家共话楼市新趋势 房地产市场结构需进一步优化

- 2021年经济领域的三大工作重点

- 遏制炒房行为可以从完善住房制度入手

- 重视经济安全,并用“双循环”战略应对贸易逆全球化

- 重视经济安全,并用“双循环”战略应对贸易逆全球化

- 楼市“三道红线”的政策威力初步显现

- 尹中立:注册制成功的关键在于退市制度能否有效运行

- “抢人”更要留人 关键看城市发展机会和营商环境

- 市场炒作绩差股的深层次原因分析

- 为什么要对地产龙头企业财务指标进行监控

- 无风险收益率下行是股市走强的重要原因

- 双循环战略将更加倚重资本市场

- 防止经营性贷款流入房地产市场,坚持房住不炒

- 推动中国科技创新是科创板的重要使命

- 股市打假不仅需要新技术,更需要新机制

- 疫情引发金融冲击波 转机或许已在路上

- 指数编制方法的适时修订,开启了上证综指的新征程

- 金融市场,在震荡中前行

- 重视深圳房价涨与房租降背离现象

- 股票指数涨幅为何跟不上GDP的增速?

- 美联储救市的效果考量

- 新形势下的底线思维

- 疫情全球蔓延,需密切关注债务风险

- 疫情结束前人民币是资本唯一的避风港!

- 美联储降息利好中国股市与楼市

- 房地产政策如何应对新冠疫情的影响

- 加大土地供应 确保楼市稳定运行

- 2020年房地产市场展望

- 2020年股市投资展望

- 房地产调控政策的效果正在显现

- 房地产政策导向出现新变化释放了哪些信号

- 科创板制度优势凸显

- 今年下半年房价将稳中趋降

- 注册制改革的关键是退市制度有效实施

- 制度创新,为科创板“保驾护航”

- 如何让上市公司真正守住“四条底线”?

- 一季度政治局会议释放新信号,实行预期调控

- 科创板制度创新评价及建议

- 因城施策是房地产调控方式的创新

- 科创板需要建立完善的做空机制,以投机遏制投机

- 2019年房地产金融风险前瞻

- 股市是否应该恢复T+0?

- 房地产业集中度仍有提升空间

- 房企竞逐新领地一一物业管理

- 稳定市场预期 防范房地产市场风险

- 楼市运行出现明显变化

- 官方公布房价数据为何与实际感受存在差异

- 一旦走入“熊市”美国经济将大概率衰退

- 用好棚改货币化政策工具

- 杠杆资金风险暴露 重振股市需对症下药

- 土地制度对住房制度的影响

- 建设楼市长效机制关键在土地制度改革

- 股市为何对商品房预售制度反应如此敏感

- 如何看待最近几年货币与房价的背离?

- 多原因导致租金上涨 建议三举措加强监管

- 房租上涨的逻辑

- 尊重股市自身的逻辑

- 房地产去库存政策应该逐步退出

- 新的住房制度从深圳启航

- 完善退市制度将加速壳公司贬值

- “独角兽”公司的股价为什么会腰斩

- 金融去杠杆对股市的影响及应对之策

- 美股是中美贸易摩擦的软肋

- 美国股市的最大风险来自利率的提高

- 尽快退出房地产去库存政策

- 应该严控金融类公司的IPO

- 注册制改革延期对二级市场将产生何种影响

- 股市出现暴跌的原因分析

- A股今年或逆转 国家队资金调整

- 股灾再现不仅与金融去杠杆政策有关

相关研究中心成果

Relate ResearchCenter Results

- 暂无 Null