订阅邮件推送

获取我们最新的更新

LPR Reform Propels Interest Rate Liberalization

1. Introduction

China has implemented strictly regulated interest rates for an extended period since the reform and opening-up in 1978. Back then, China’s financial market was in its infancy, and a complete interest rate system was yet to take shape. China’s market-oriented economic reforms coincided with deepening interest rate liberalization. As of July 20, 2013, China has fully deregulated lending interest rates for financial institutions as part of its gradualist reforms. By removing the floor of 0.7 times for the lending rate floating range, China has allowed its financial institutions to set lending rates based on market forces, giving play to the role of the market mechanism in the formation of interest rates.

Amid the interest rate liberalization, China has been proactively developing its benchmark interest rate system by setting the repo fixing rate, Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (Shibor), and the loan prime rate (LPR). Among them, the LPR aims to promote the role of market forces in determining lending rates for financial institutions. The LPR is the lending rate offered by commercial banks to their highest quality customers. Other lending rates can be derived by adding and subtracting basis points based on the LPR. In October 2013, China officially launched the centralized LPR quotation and release mechanism, which can be referred to as LPR 1.0.

The LPR 1.0 is the weighted average of valid LPR quotations by quoting banks on each work day after excluding the highest and the lowest rates with the balance of renminbi loans of valid quoting banks at the end of the previous quarter as a share of the total balance of renminbi loans of all quoting banks at the end of the previous quarter as the weight. The centralized LPR quotation and release mechanism is an essential component of the self-regulatory mechanism for the market-based interest rate. It marks a further development of Shibor in the credit market, and is conducive to developing a benchmark interest rate system for the financial market. It facilitates a stable transition from the central bank’s determination of the pricing benchmark to a market-based pricing benchmark. It helps increase the pricing efficiency and transparency of credit products offered by financial institutions, and enhance their independent pricing power. It also contributes to the improvement of the central bank’s interest rate regulation mechanism. After the centralized LPR quotation and release mechanism comes into effect to guide financial institutions in setting reasonable lending rates, the PBC will continue to release the benchmark lending rate for a certain period to ensure the steady and orderly implementation of interest rate liberalization and provide a transition period for the LPR’s development and improvement.

After canceling the ceiling and floor of lending rates, China’s central bank retains the benchmark deposit and lending rates as monetary policy instruments. In this manner, China has formed a complex interest rate mechanism comprising fully market-based bond rates and short-term lending rates highly sensitive to the economic climate, theoretically fully flexible deposit and lending rates for commercial banks, and the central bank’s regulated benchmark deposit and lending rates as monetary policy instruments.

By setting the market-based deposit and lending interest rates, China’s financial regulators intended to enhance the risk-based pricing power of commercial banks. Yet the reality over the past few years shows that the lending rate of Chinese banks remains very rigid. Based on the central bank’s information, most commercial banks still referenced the benchmark lending rate in issuing loans. Some banks jointly set an implicit floor by applying a multiple to the benchmark lending rate, such as 0.9 times. Since 2015, China’s commercial banks have maintained very stable benchmark lending rates, although the bond market yield has experienced two rounds of downward-upward-downward cycles.

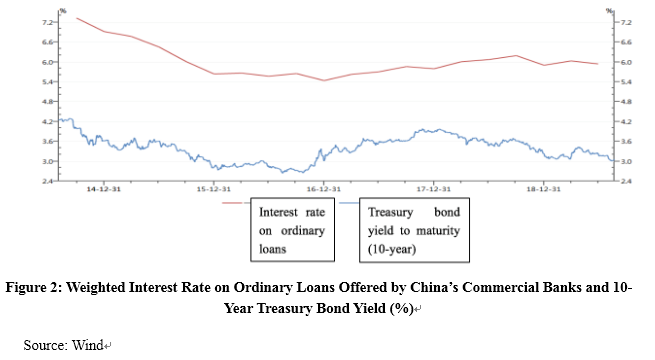

In about four years since 2015, the LPR for commercial banks has stayed at the level of 4.31% (see Figure1), which impedes the transmission of market-based interest rates to the real economy. As the 10-year treasury yield rate dropped in 2017 and 2018, commercial banks raised the weighted interest rate for ordinary loans, which goes against the central government’s policy intention to make access to capital less costly for businesses (see Figure2).

2. LPR Reform

To facilitate interest rate liberalization, China’s financial regulators face a pressing task to make the LPR more sensitive to economic performance, market liquidity, and risk profile. Many options are on the table. The simplest option is for the central bank to do away with the ineffective benchmark lending rate, and force commercial banks to seek a more market-based LPR pricing benchmark. Another option is to reform the LPR mechanism while the central bank creates a new pricing benchmark that reflects the financial market status and more effectively transmits the central bank’s monetary policy intentions. Based on the comparison, the central bank followed the latter option.

The current round of LPR reform comprises the following core elements:

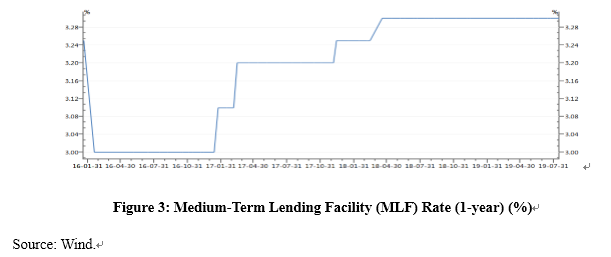

First, the LPR quotation method is transformed into adding basis points to the interest rate of open market operations. Original LPR quotations were made mostly referencing the benchmark lending rate, which, apart from being a regulated interest rate inconsistent with market-based operations, has ceased to function in the central bank’s monetary policy toolbox since 2016. Therefore, it cannot reflect the central bank’s policy intentions nor changes in market liquidity. After the reform, the quoting banks will add basis points to the interest rate of open market operations, which mainly refers to the medium-term lending facility (MLF) rate according to the central bank’s definition. MLF usually has a term of one year, and comprises part of the average marginal cost of capital for the banks. The extent to which basis points are added to the benchmark interest rate is subject to such factors as the cost of capital, supply and demand, and risk premium. Thus, the LPR will be more market-based and flexible.

Second, LPR with maturities longer than five years will also be made available in addition to the current one-year LPR. Such long-term LPR will provide commercial banks with interest rate pricing for long-term loans such as housing mortgage loans, and facilitate the future transition of pricing benchmark for floating-rate loan contracts towards LPR.

Third, increase number of quoting banks and increase the representativeness of quoting banks. The reform has expanded LPR quoting banks from ten nationwide banks to 18 banks by including two city commercial banks, two rural commercial banks, two foreign-funded banks, and two private banks. The new quoting banks are small and medium-sized banks with relatively significant influence, pricing power, and effective services to small and micro businesses in the lending market of comparable banks. Their inclusion can increase LPR’s representativeness to some extent.

Lastly, the reform has reduced quoting frequency from daily quotation to quotation once every month for quoting banks to attach greater importance and improve LPR’s quoting quality.

Aside from the four core elements, the central bank has created three supporting mechanisms:

First, it requires the banks to reference LPR pricing in issuing new loans, and adopt LPR as the pricing benchmark for floating-rate loan contracts. That is to say, LPR will replace the central bank’s original benchmark lending rate to become a new benchmark lending rate for commercial banks.

Second, regulators and the market-based interest rate pricing self-regulatory mechanism will supervise banks, and enterprises may report the banks’ concerted practices to set an implicit interest rate floor for loans.

Third, the central bank incorporates banks’ use of LPR in setting lending rates and lending rate competition into the macro-prudential assessment (MPA) to supervise banks in using LPR pricing.

Transformed from the original LPR, the new LPR can be referred to as LPR 2.0.

The recent LPR reform was carried out in the context that the government repeatedly called for reducing financing cost for the real economy, but commercial banks kept their benchmark lending rate inflexible. The central bank believes that the market-based LPR reform may reduce the actual lending rate. After the significant rate cuts carried out earlier, the reform will make LPR more reflective of the market-based interest rate. As market forces play a more significant role in determining the LPR, banks will find it harder to set an implicit lending rate floor through concerted practices, making it possible to reduce lending rates.

3. Future Outlook

The recent round of LPR reform marks the central bank’s new attempt to propel China’s interest rate liberalization and create conditions for interest rates to be on track. However, in my view, the following questions warrant further discussion for a competitive market mechanism to play a decisive role in the pricing of loans and make lending rates fully and timely reflect macroeconomic changes.

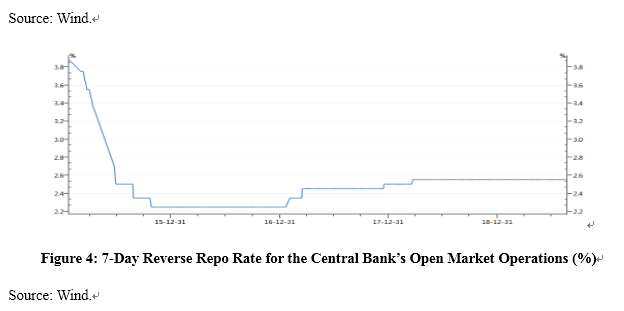

First, LPR benchmark: The LPR reform no longer follows the central bank’s benchmark lending rate, thus creating conditions for the central bank to abandon the benchmark lending rate. As the MLF-dominated open market rate becomes LPR’s quotation benchmark, MLF rate should better reflect macroeconomic performance for LPR to be more reflective of changes in the external environment. As can be seen from Figure 3 and Figure 4, however, neither the MLF rate nor the central bank’s reverse repo rate kept pace with changes in the market-based interest rate. Despite falling bond market rates since 2017, MLF and reverse repo rates have been on the rise.

Even if MLF serves as LPR’s quotation benchmark as it did in the past, actual LPR may not reduce with changing bond market yield as long as MLF and reverse repo rates as policy instruments represent the central bank’s monetary policy intentions. If the LPR serves as the pricing benchmark for the lending rate of commercial banks, whether the LPR will reduce with falling market-based interest rate is doubtful as long as MLF rate is stable.

Second, the central bank found that when executing the lending rate, some commercial banks set an implicit floor by applying a multiple to the benchmark lending rate (such as 0.9 times) through concerted actions, which impedes the market-based lending rate. In this sense, the collective practices of commercial banks to set lending rates are acts of collusion that seriously conflict with market competition, which will harm competition and pricing efficiency and the interests of borrowing customers.

Future interest rate liberalization reforms must make the following efforts:

First, abolish the benchmark lending and deposit rates as soon as possible. Despite their previously important role, the central bank’s benchmark lending and deposit rates have failed to function in China’s monetary policy since 2015, creating a barrier for commercial banks to set market-based lending rates. Over the past decade, the central bank has maintained a very high interest spread in setting the benchmark lending and deposit rates, enabling commercial banks to profit but discouraging them from effectively pricing loan risks.

Second, the new LPR mechanism should make it more flexible for commercial banks to price their loans, and ensure certain flexibility in the LPR benchmark. Regretfully, the central bank’s MLF rate has deviated from China’s economic situation over the past few years. Despite slowing growth and an escalating trade war with the US, China’s MLF rate has increased. Thus, improving the MLF mechanism becomes an essential link in the interest rate liberalization under the new LPR mechanism.

Lastly, the improvement of interest rate liberalization requires legal penalties. The central bank has found that some commercial banks have set an implicit interest rate floor in collusion. Collusive pricing is a severe violation of the law in any country with market-based interest rates. It harms the interests of financial consumers and borrowers. According to the central bank, both regulators and the market-based interest rate self-regulatory mechanism will supervise banks, and enterprises may also report banks’ concerted practices in setting lending rates. Without legal penalties, however, the concerted pricing of the lending rate is hard to avoid. To improve the socialist market economy, we need a legal system to fight monopoly and protect fair market competition.

作者相关研究

Author Related Research

- 暂无 Null

相关研究中心成果

Relate ResearchCenter Results

- 暂无 Null